By MICHAEL SCHREIBER

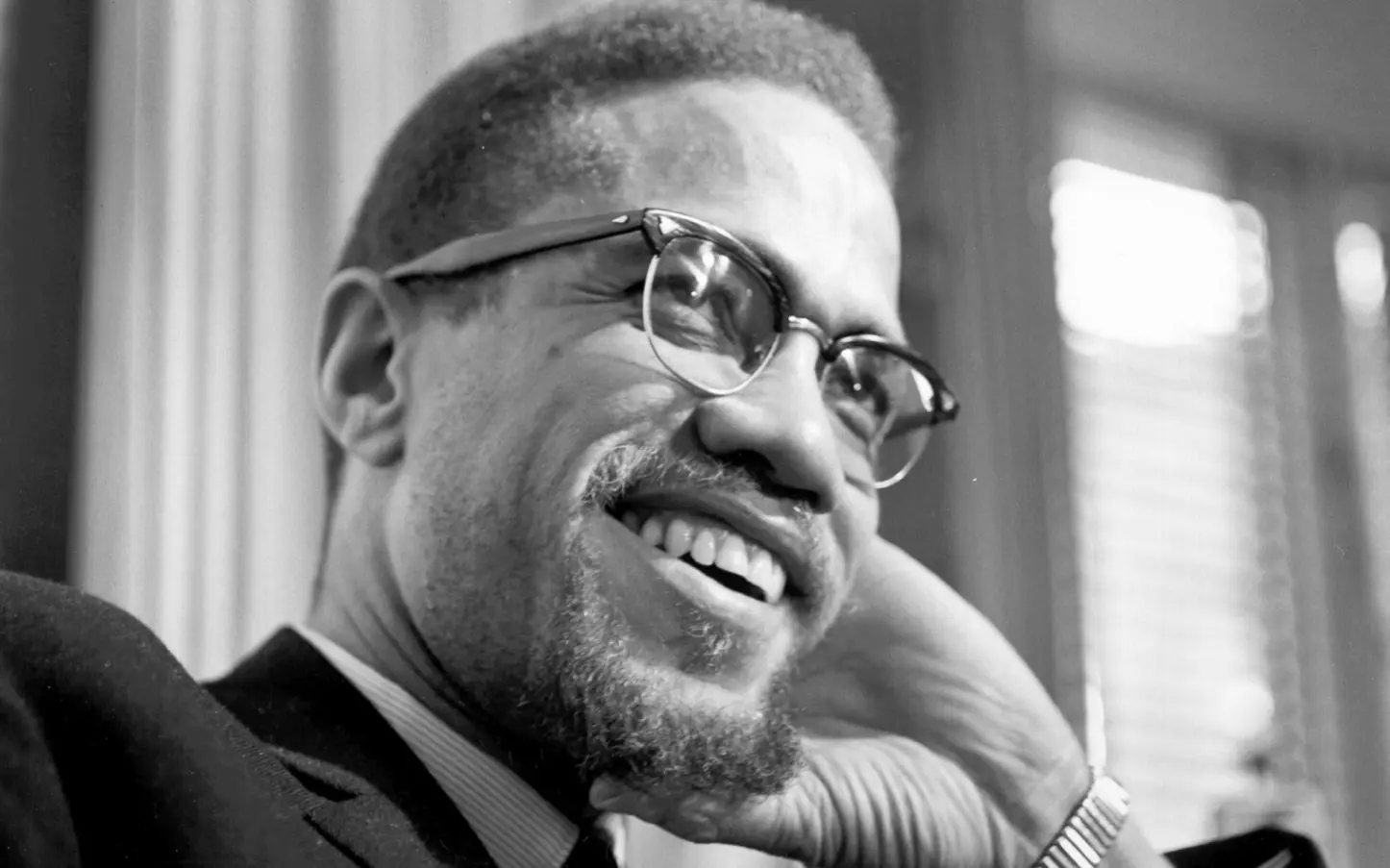

May 19 marks the 100th birthday of Malcolm X—a seminal political leader of the 20th century. Malcolm’s ideas and teachings, as expressed in his speeches and interviews, have had an influence lasting far beyond his own time—not only on the movement for Black liberation in the United States but on liberation movements worldwide.

Malcolm continued to reshape his beliefs and his actions throughout his life—often in the face of great adversity. Even in his final year, before he was struck down by an assassin’s bullet in February 1965, Malcolm continued to refine his views on strategy and program. After trips to Africa and the Middle East, where he met with leaders of the anti-colonial struggle, he began to emphasize internationalist and anti-capitalist conclusions in his speeches. At the same time, he set about to build an activist organization based on a comprehensive program for Black liberation—the Organization for African American Unity.

There is not sufficient space here to review the entirety of Malcolm’s political development or the breadth of his thought. Since it is the centennial of his birth, I thought it might be useful to dwell on his early years, before skipping to the momentous last year of his life—at which time I had the opportunity to meet Malcolm and to hear him speak.

Malcolm’s early life

There is no doubt that Malcolm X’s thinking was molded in some ways by the racism, violence, and poverty that his family had suffered during his childhood. His parents also provided a model of how to stand up against oppression and fight back.

Malcolm was born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Neb., the son of Earl and Louisa Little. His parents were supporters of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a pan-Africanist movement advocating that the Black community work toward self-sufficiency and nation-building. As field organizers for the Garvey movement, the Littles moved from Philadelphia to Omaha in 1921 in order to start a branch of the UNIA in the Midwestern city.

In early 1925, several months before Malcolm’s birth and while Earl Little was out of town, his mother had to confront a gang of torch-bearing Klansmen, who came to their house in the middle of the night to threaten the family with dreadful consequences if they did not leave town. The Littles moved north the following year, but could not escape racist violence. In 1929, their house in East Chicago, Ind., was firebombed and destroyed by white racists. Malcolm’s father was initially charged with the bombing (allegedly for the insurance money), but the authorities were unable to make the weak charges stick, and he was released.

Two years later, now living in Lansing, Mich., Earl Little was killed. Although the police report stated that he had been run over by a streetcar in an unfortunate “accident,” the circumstances suggested that he had been murdered. According to Malcolm’s biographer, Manning Marable (Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention),* his father’s murder haunted him the rest of his life; Malcolm referred to it in a 1960s interview by Chicago reporter Jim Hurlbut as being carried out by the Klan.

The family was quickly reduced to poverty. By 1939, Malcolm’s mother had fallen into deep depression and was ordered into a mental institution. Within a couple of years, Malcolm, now 16, was entrusted into the care of his half-sister, Ella, who lived in Boston. Malcolm made friends there who introduced him into the life of hustlers, numbers runners, and petty gangsters.

For a while, at the start of World War II, Malcolm got a job as a cook on railroad trains, and soon moved from Boston to Harlem. At the time, the Black community in Harlem was engaged in numerous political actions due to racial tensions—culminating in the Aug. 1, 1943, rebellion and riot that broke out after a cop shot a Black serviceman in uniform. However, Malcolm continued his life as a hustler, often selling reefers on the trains, and rarely, if ever, got involved in political activities.

And yet, one of his friends, Clarence Atkins, recalled later that Malcolm spoke frequently about Black nationalist ideas when he was working at Jimmie’s Chicken Shack in 1942-43. “He would talk often,” Atkins explained, “about how his father used to get brutalized and beat up on the corner selling Marcus Garvey’s paper, and he would talk a lot about Garvey’s concepts in terms of how they would benefit us as a people” (Marable, p. 52).

Malcolm continued in a life of crime for the next few years—selling drugs, pimping, running numbers, and burglary jobs. For a while, he played drums and danced in a nightclub act. After several burglaries on the outskirts of Boston, Malcolm and his gang were captured and convicted. Malcolm received a sentence of four concurrent periods of eight to 10 years in prison. He knew that his harsh sentence was imposed in part because he had a white girlfriend as his accomplice, and thus he was seen as showing contempt for white-supremacist moral standards.

Becoming Malcolm X

While serving time in the notorious Charlestown prison in Massachusetts, the rebellious Malcolm gradually came to realize, perhaps opportunistically, that he could improve his living conditions, including a transfer to a less harsh facility and possibly an early parole, if he tried to appear more cooperative—at least outwardly—with the “rules” that the prison imposed upon inmates. Simultaneously, he strived to educate himself, even reading the dictionary to improve his command of the English language. Once he been transferred to a prison with a full library, he devoured the writings of modern Black scholars as well as the ancient philosophers. He read books recounting the history of the slave trade, the colonial rebellion in the East, and much more. “I could spend the rest of my life reading,” he later reflected. “I don’t think anybody ever got more out of going to prison than I did.”

His drive for self-improvement was given new impetus after his brothers and sisters wrote to Malcolm that most of the family had converted to Islam. More specifically, they had begun to follow a particular sect, the Nation of Islam, which had grown up during the previous decade and was now led by a former Garveyite, Elijah [Poole] Muhammad. Though Malcolm remained skeptical at first, they urged him to write a letter to Elijah Muhammad for more information. Muhammad answered Malcolm’s letter, and eventually, Malcolm was writing to the NOI leader daily.

After becoming a member of the NOI, Malcolm saw his own life in a new light and with a new purpose. He set about to convert other prisoners. By early 1950, the group of Muslim inmates began to demand changes by the prison authorities such as menus to accommodate the dietary restrictions of their faith. The prison officials considered their demands as disruptive, and transferred Malcolm and other Black Muslims back to the more restrictive prison at Charlestown. There, Malcolm continued his agitation for better conditions, while writing to former friends and associates that he was now dedicated to Black emancipation and rejected the values of white society (the NOI at that time considered white people to be “devils”). By December 1950, he had eschewed the slave name “Malcolm Little” and signed his letters “Malcolm X.”

Tensions grow in the Nation of Islam

On July 1, 1952, Malcolm X was released from prison. He moved to Detroit, where he resided in the home of his brother Wilfred and his wife Ruth. Malcolm worked for a while in the auto industry but soon was appointed as a full-time recruiter for the Nation of Islam, traveling throughout the Eastern portion of the country. He helped to establish a temple in Boston and was then assigned as minister of the NOI temple in Philadelphia. From there, in 1954, Malcolm was called on to head up Temple No. 7 in Harlem. Soon he had established a reputation as Elijah Muhammed’s most loyal, energetic, and charismatic lieutenant.

The New York mosque was small compared to those in other cities; as a quasi-political group, the NOI faced competition from numerous other Black organizations based in the city. But it quickly began to grow and prosper under Malcolm’s leadership. Nationally, the NOI also experienced rapid growth—with hundreds of new applicants for membership a week.

This was just as the civil rights movement against Jim Crow segregation was getting under way and finding itself brutally confronted by Southern white racists and police. Although by the beginning of the 1960s, the civil rights movement had been generating sympathetic actions all over the country, the NOI, under Elijah Muhammad’s strict instructions, refused to get involved.

Then, on April 26, 1957, three NOI members tried to intervene into an incident in which New York City cops were unmercifully beating a Black man in the street. The Muslims were arrested by the police for their interference. Malcolm and his associates managed to lead a delegation to the station house, backed by a protesting crowd of at least 4000 people. All three Muslims were eventually acquitted, later winning a lawsuit against the NYPD for $70,000.

Marable writes (pp. 127-129) that this protest revealed the contradictions brewing in the Nation of Islam, which culminated in Malcolm’s eventual rupture with the NOI: “Elijah Muhammad could maintain his personal authority only by forcing his followers away from the outside world; Malcolm knew that the Nation’s future growth depended on its being immersed in the black community’s struggles of daily existence. … Eventually, he would have to choose: whether to remain loyal to Elijah Muhammad, or to be ‘on the side of my people.’”

Five years later, on April 27, 1962, an even more dire incident took place in Los Angeles, when cops shot seven unarmed Black Muslims, killing one and maiming another for life. The cops then arrested 16 NOI members on false charges of “criminal assault against the police.” Muhammad sent Malcolm X to Los Angeles to deal with the case. Malcolm managed to supervise a vigorous defense campaign, even addressing white people and other religious faiths to join the protests and donate funds. Plans were put into operation to build a broad national campaign to defend the Muslims. But suddenly and with no explanation, the united-front defense effort was called off. Instead, the decision was made—most likely from the top leadership of the NOI—to fight the charges merely through the courts.

George Breitman comments in “The Last Year of Malcolm X,”** that that event was the first time that the existence of two tendencies within the Nation of Islam became evident to some NOI members. However, the tensions were probably not obvious to most people. As late as 1963, Muhammad appointed Malcolm the organization’s first “national minister,” and so, ostensibly, the two seemed to be in accord.

Yet, as Breitman writes, Malcolm “stretched the bounds of Muhammad’s doctrine to the limit, and sometimes beyond. He introduced new elements into the movement, not only of style but of ideology.” As an example, Breitman cites a quotation in The New York Times (Nov. 8, 1964) by James X, who replaced Malcolm as head of the New York mosque after the split, and Henry X. “It was Malcolm who injected the political concept of ‘black nationalism’ into the Black Muslim movement,” The Times quoted them as saying and added, “which they said was essentially religious in nature when Malcolm became a member.”

The incident that directly precipitated the split between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad came at a forum in New York on Dec. 1, 1963, nine days after the assassination of President Kennedy. During the discussion period, Malcolm was asked about the assassination. In responding, he placed the murder within the pervasive climate of hate and violence in the U.S. that was often forged or tolerated by the ruling interests. Now, he said, the “chickens have come home to roost.”

The next day, in Malcolm’s regular monthly meeting with Muhammad, the NOI leader called the Kennedy statement “ill timed” and suspended Malcolm for 90 days. Breitman comments that it soon became apparent that the suspension was to be more than 90 days, and possibly permanent. And Malcolm got wind of the fact that one Muslim leader had been calling for his death. He believed, Breitman relates, that “any death-talk for me could have been approved of—if not actually initiated—by only one man.” After much soul-searching, on March 8, 1964, he announced that he was leaving the Nation of Islam and starting a new organization. He stated that the Black Muslim movement “had ‘gone as far as it can’ because it was too narrowly sectarian and too inhibited.”

“I am prepared,” he was quoted in The New York Times (March 9, 1964) as saying, “to cooperate in local civil rights actions in the South and elsewhere and shall do so because every campaign for specific objectives can only heighten the political consciousness of the Negroes and intensify their identification against the white society.”

He continued, “Good education, housing, and jobs are imperatives for Negroes, and I shall support them in their fight to win these objectives, but I shall tell the Negroes that while these are necessary, they cannot solve the main Negro problem.” He indicated that what was necessary was a real revolution.

Militant Labor Forum speech

On April 13, Malcolm left on a five-week journey to Mecca and to Africa, where he met with the leaders of some of the newly independent countries. The trip helped to clarify and solidify his thinking on many questions. I heard him speak on May 29, shortly after he returned to the United States.

The meeting, at the Militant Labor Forum, within the headquarters of the Socialist Workers Party in Manhattan, had been called to address questions about a mysterious (or fictional) “hate gang” called the “Blood Brothers.” The New York dailies had been printing lurid stories about this group, allegedly consisting of “dissident Black Muslims” and dedicated to the objective of killing white people. A panel of Black leaders had been assembled for the forum, including leaders of CORE and the Harlem Action Group; Clifton DeBerry, the SWP candidate for U.S. president; and James Shabazz, the secretary to Malcolm X. It was explained to me that the forum organizers had originally wanted Malcolm himself to speak, but that since he was still on his Africa trip at the time the forum was organized, they asked Shabazz instead.

I helped to set up the chairs for the forum and went into the hallway, probably to do a little sweeping. Suddenly, I was startled by seeing Malcolm X clambering up the stairs from the street—with a big grin on his face. He was closely followed by two associates. Malcolm told me that he had come to speak in place of James Shabazz. I asked him to please wait a moment and hurried into the next room to summon someone to greet him.

I remember that Sylvia Weinstein and a couple of other SWP members came out to welcome Malcolm. Sylvia already knew Malcolm X; she had helped to set up the meeting between Fidel Castro and him at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem in September 1960. Sylvia introduced Malcolm to me, saying, “This is one of our young comrades.” Of course, at 19 years old, I had only come around the Socialist Workers Party very recently and was still learning the basics of revolutionary socialism. But Malcolm gave me a gracious acknowledgement that I took as indicating that he accepted me as his comrade as well.

People began to stream into the forum. The atmosphere was electric, and the hall was soon filled; it was standing room only. I stood far in the back of the crowd but I can still visualize the panelists seated at a long table and Malcolm at the microphone.

Malcolm began by offering an apology for his late appearance at the forum, but said that he could not resist the opportunity to speak. He then reported that, just as “they say that travel broadens your scope,” he had had that experience during his recent travels in the Middle East and Africa. “While I was traveling,” he said, “I noticed that most of the countries that had recently emerged into independence have turned away from the so-called capitalistic system in the direction of socialism. So out of curiosity, I can’t resist the temptation to do a little investigating wherever that particular philosophy happens to be in existence or an attempt is being made to bring it into existence.”

He returned to this issue during the question period: “You can’t have capitalism without racism. And if you find one [i.e., a person who doesn’t support racism] and you happen to get into conversation, and they have a philosophy that makes you sure they don’t have this racism in their outlook, usually they’re socialists or their political philosophy is socialism.”

In regard to the “Blood Brothers,” Malcolm said that the first time he had heard of them was when he was in Nigeria. He did not know whether the group existed, but he said that the question ought to be asked, “Should they exist?” “As far as I’m concerned,” he stressed, “everybody who has caught the same kind of hell that I have caught is my blood brother.”

He then drew the question back toward the issue of police brutality: “A Black man in America … doesn’t live in any democracy. He lives in a police state.” He said that he had visited the Casbah in Casablanca and in Algiers together with some of the “blood brothers” there. “They took me down into it and showed me the suffering, showed me the conditions they had to live under while they were being occupied by the French. … And they also showed me what they had to do to get those people off their back. The first thing they had to realize was that all of them were brothers; oppression made them brothers.

“They lived in a police state. Algeria was a police state. Any occupied territory is a police state; and this is what Harlem is. … The police in Harlem, their presence is like occupation forces, like an occupying army.”***

These views were consistent with the often quoted line by Malcolm X: “Freedom by any means necessary.” He firmly opposed violent aggression but recognized that violence must not be excluded when necessary for self-defense and for liberation.

Malcolm also remained an internationalist until his dying day. Just a month before his assassination, Malcolm pointed out, “It is incorrect to classify the revolt of the Negro as simply a racial conflict of Black against white or as a purely American problem. Rather, we are today seeing a global rebellion of the oppressed against the oppressor, the exploited against the exploiter.”

Malcolm’s daughters file suit

The life of Malcolm X was cut off prematurely; he was only 39 when he was killed on Feb. 21, 1965, while beginning a speech at Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom, with his family in attendance. The shooting was blamed on people within the Nation of Islam; three men were convicted of involvement in the act, but two of them were exonerated in 2021 after investigators took a fresh look at the case and determined that the evidence was shaky. There is little doubt that government authorities knew in advance that there would be an attempt on his life. Police arrested Malcolm’s security detail days before the assassination, and their own uniformed officers were unusually absent from attending Malcolm’s Feb. 21 speech.

In November of last year, three daughters of Malcolm X—along with the Malcolm X estate—filed a $100 million lawsuit in Manhattan federal court that claimed that federal and city agencies were involved in the assassination of their father. The suit states that government agents “actively concealed, condoned, protected, and facilitated” the killers.

On May 19, 2025, the attorney for the lawsuit, Ben Crump, spoke on “Democracy Now” of the continued fight for justice for Malcolm X. He charged that the assassination was “an intentional effort at the behest of the leaders of our government—the New York police department, the FBI, the CIA, all the way to the very top. And so, 60 years later, on what would have been his 100th birthday, we implore the federal government to release all of the FBI papers on Malcolm X.”

For further reading:

Malcolm X, Black nationalism and socialism

By GEORGE NOVACK Malcolm X was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965. On this anniversary of the tragedy, we are republishing this review of George Breitman’s book, “The Last Year of Malcolm X: The Evolution of a Revolutionary.” George Novack, a leading member of the Socialist Workers Party and the author of many books on Marxist philosophy

Sources:

* Marable, Manning, “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention.” (New York: Viking Press) 2011.

** Breitman, George, “The Last Year of Malcolm X.” (New York: Merit Publishers) 1967.

*** Quotations from the May 29, 1964, meeting are contained in Breitman, George, ed., “Malcolm X Speaks.” (New York: Grove Press edition) 1966, pp. 64-71.